A new study reveals that when one partner faces a stressful situation, the other’s body often follows suit—but your deep-seated attachment style determines if you tune in or tune out.

Imagine watching your romantic partner navigate a high-stakes job interview. They’re under a harsh spotlight, fumbling for words, their anxiety palpable. Do you feel your own pulse quicken? A knot forming in your stomach? This isn’t just sympathy; it’s a phenomenon known as "empathic stress," where one person’s stress becomes contagious. Neuroscientists have long been fascinated by this deep-seated connection, but a recent study digs even deeper, asking a crucial question: Does our fundamental approach to relationships—our attachment style—dictate how strongly we absorb a partner’s stress? The answer, it turns out, is written in our hormones.

The Science of Shared Stress and Attachment

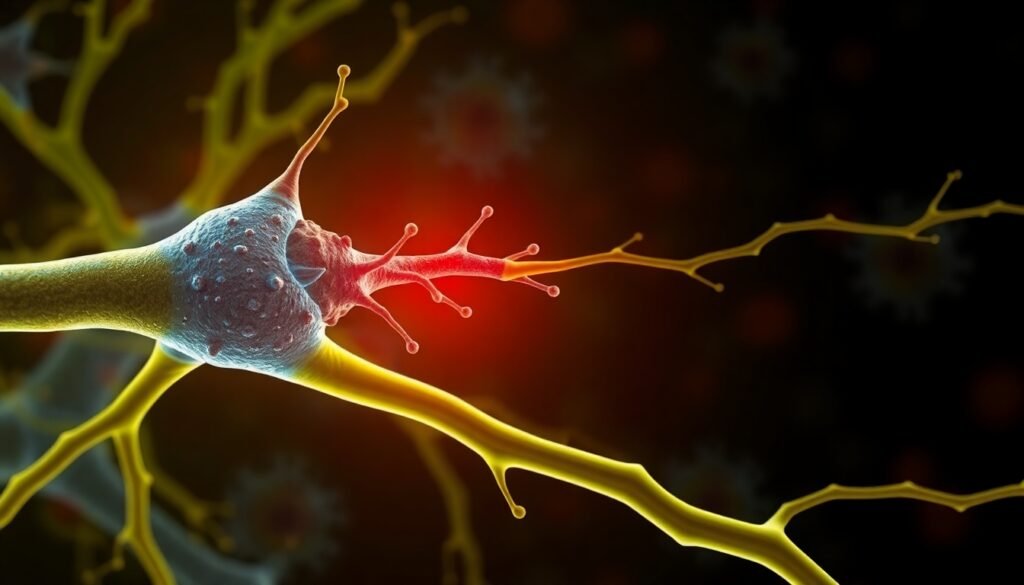

Our bodies are wired for connection. When we witness someone else in distress, especially a loved one, our own physiological systems can kick into gear. This is empathic stress, and it comes in two main flavors. The first is stress resonance, where your biological stress response, like the release of the hormone cortisol, mirrors that of the person under pressure. If their cortisol spikes, yours does too. The second is vicarious stress, which is more about your own personal sensitivity; you might feel stressed just by the situation, regardless of how your partner is actually coping.

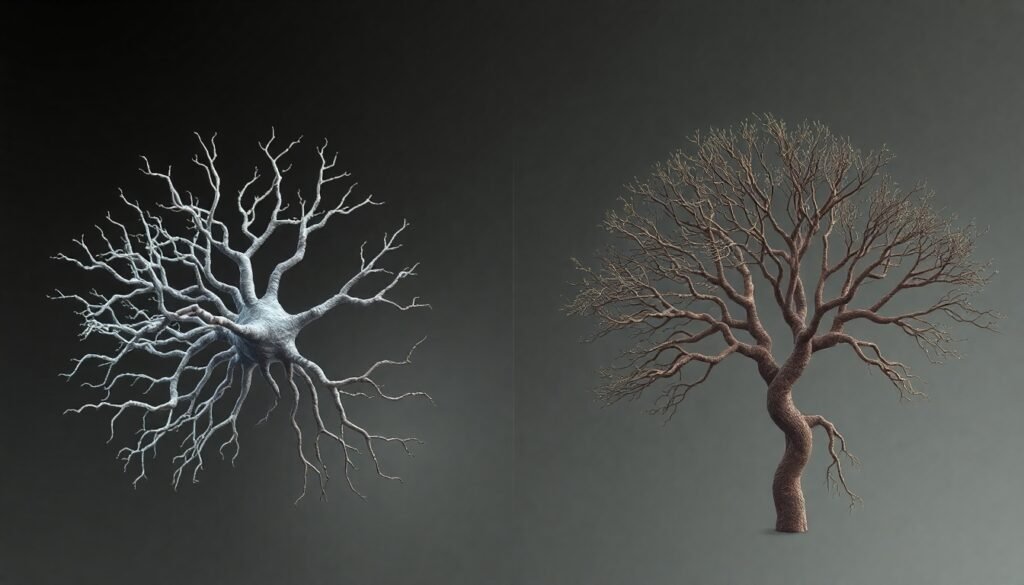

These responses are governed by our internal "blueprints" for relationships, known as attachment styles. Forged in childhood, these styles shape how we connect with others in adulthood. Individuals with a secure attachment style are generally comfortable with intimacy and trust, viewing themselves as worthy of love and others as reliable. In contrast, those with an insecure-dismissing attachment style often prioritize independence, emotionally distancing themselves and suppressing their need for closeness to avoid vulnerability. Could these fundamental differences in how we relate to others change how our bodies react to their pain?

Putting Empathic Stress to the Test

To find out, researchers designed a clever experiment involving dozens of heterosexual couples. In each pair, one person was randomly assigned to be the "target" and the other, the "observer." The target was then subjected to the Trier Social Stress Test (TSST), a notoriously effective stress-inducer that involves giving an impromptu speech and performing difficult mental arithmetic in front of a panel of stern-faced judges.

While the target sweated under the psychological pressure, the observer simply watched from the same room, instructed not to interact. Throughout this process, scientists collected a wealth of data from both partners: subjective reports of anxiety, continuous heart rate monitoring, and, most importantly, saliva samples to measure levels of cortisol—the body’s primary long-term stress hormone. Before the stress test, each observer also completed the Adult Attachment Interview, a detailed, gold-standard assessment to determine their attachment style.

The Surprising Sync: A Tale of Two Attachment Styles

The results were striking. The researchers confirmed that empathic stress was real; on average, observers’ cortisol levels rose in proportion to their partners’ stress. But the critical discovery came when they factored in attachment style.

Couples with a securely attached observer showed significantly higher cortisol resonance. Their stress hormone levels rose and fell in remarkable synchrony with their partner’s. It was as if their physiological stress systems were tuned to the same frequency, creating a shared biological experience.

Conversely, this physiological mirroring was absent in couples where the observer had an insecure-dismissing attachment style. While they might have felt concerned on a conscious level, their bodies did not sync up with their partner’s hormonal stress response. Their physiological systems remained independent, reflecting their characteristic emotional distance.

Why the Difference? Attunement vs. Deactivation

This divergence makes perfect sense from an attachment perspective. Securely attached individuals hold positive views of themselves and others, allowing them to be emotionally open and attuned. Their physiological synchrony is a biological manifestation of their psychological capacity for connection and empathy. They are comfortable "feeling with" their partner, and their body reflects that.

On the other hand, insecure-dismissing individuals learn to deactivate their attachment system to maintain a sense of self-reliance and avoid the perceived messiness of emotional dependency. This strategy of suppression isn’t just mental; it’s physiological. By not syncing up with their partner’s stress, their bodies are enacting the same emotional distance they cultivate in their relationships. It’s a powerful demonstration of how our deepest relational patterns are embodied, right down to our hormonal responses.

A Double-Edged Sword? The Pros and Cons of Resonance

Is this heightened stress resonance in secure couples a good thing? The answer is complex.

In the face of an acute, external threat—like the one in the study—it can be highly adaptive. This shared physiological state may foster a deeper understanding of the partner’s experience, enhance feelings of closeness, and mobilize the observer to provide effective support once the stressful event is over. It helps the couple function as a cohesive unit.

However, the researchers caution that this same trait could become a liability in situations of chronic stress. Imagine living with a partner who has a demanding, high-stress job or a chronic illness. If a securely attached person’s body is constantly syncing with that sustained stress, they are subjected to a prolonged elevation of their own cortisol. Over time, this "second-hand" stress could lead to a dysregulated stress system, burnout, and an increased risk for the very same stress-related health problems their partner faces, from anxiety disorders to cardiovascular disease.

Conclusion: Your Relationship Style Is in Your Biology

This research provides compelling evidence that our attachment style—our internal model for how relationships work—has a profound and measurable impact on our biology. For those with a secure attachment, love and connection mean their bodies literally tune into their partner’s distress. This can be a source of incredible strength and resilience for a couple, but it also highlights a potential vulnerability.

Understanding this link between attachment, empathic stress, and health is more than an academic exercise. It opens the door to developing targeted interventions to help couples navigate stress more effectively, promoting not only healthier relationships but also healthier individuals. It reminds us that the bonds we form are not just in our hearts and minds; they are deeply embedded in our physiology.

Reference

Marheinecke, R., Blasberg, J., Heilmann, K., Imrie, H., Wesarg-Menzel, C., & Engert, V. (2025). Securely stressed: association between attachment and empathic stress in romantic couples. Scientific Reports. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13970-9