New research reveals that the ‘feel-good’ chemical does more than just signal pleasure—it actively shapes how each of us learns, creating personalized pathways to expertise.

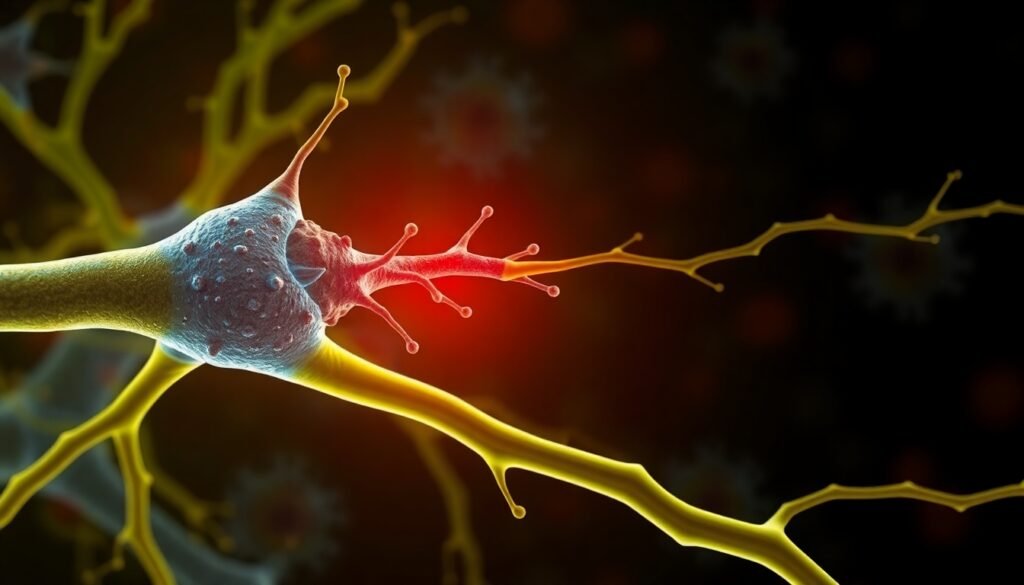

Think about the last time you tried to learn something truly difficult—a new language, a musical instrument, or a complex sport. The journey was likely filled with breakthroughs, frustrating plateaus, and unique ‘aha!’ moments. We often attribute success to practice and persistence, but what if there’s a deeper, more personalized process happening inside our brains? For decades, the neurotransmitter dopamine has been cast as the brain’s simple reward signal, a chemical pat on the back for a job well done. But a groundbreaking study is recasting dopamine in a far more sophisticated role: not just as a cheerleader, but as a personal tutor, meticulously sculpting our neural pathways based on our individual learning strategies.

Traditionally, neuroscience has explained learning through the concept of a "reward prediction error" (RPE). In this model, dopamine neurons fire when a reward is better than expected, stay quiet when it’s as expected, and decrease their firing when a reward is worse than expected. It’s a powerful mechanism for fine-tuning behavior in the short term. However, this one-size-fits-all framework struggles to explain the sheer diversity and complexity of long-term skill acquisition. Why do two people learning the same skill develop entirely different techniques? Why do we hit learning plateaus that feel impossible to overcome? The classic RPE model falls short of capturing this rich, individual tapestry of learning.

To unravel this mystery, a team of researchers led by Liebana and colleagues designed a long-term experiment to watch learning unfold in real-time. They trained mice on a visual decision-making task over several weeks. In each trial, a mouse had to turn a small wheel clockwise or counter-clockwise depending on where a visual pattern appeared on a screen. By keeping the task consistent, the scientists could isolate how each animal’s internal learning process evolved.

What they discovered was fascinating. Instead of all mice learning the task in the same way, they developed distinct and highly individualized strategies. Some mice became "balanced" learners, correctly associating both visual cues with the appropriate wheel turn. Others adopted a "lateralized" or "one-sided" strategy, essentially mastering one stimulus-response pair while largely ignoring the other. Remarkably, these early biases in their behavior were strong predictors of their entire learning trajectory. Despite taking different paths, most animals eventually reached similar levels of high performance, proving that there are many roads to mastery.

The real breakthrough came when the researchers measured dopamine activity in a specific brain region called the dorsolateral striatum (DLS), an area crucial for habit formation. At the beginning of training, dopamine signals behaved as expected, firing in response to rewards. But as the mice became more proficient, the dopamine signals began to change. They started firing in anticipation of the task-relevant visual cues, and they did so in a way that mirrored each animal’s unique strategy. In one-sided learners, dopamine activity was asymmetric; in balanced learners, it was symmetrical. This showed that dopamine wasn’t just encoding a global reward signal; it was encoding specific stimulus-choice associations contingent on the animal’s internal learning state.

To confirm that this dopamine activity was actually driving the learning, not just reflecting it, the team used optogenetics—a technique that uses light to control neurons. When they inhibited dopamine release in the DLS, the mice struggled to form effective strategies and their learning stalled, even though they remained engaged with the task. In another experiment with expert one-sided learners, the researchers artificially stimulated dopamine release right after an incorrect choice. This stimulation only helped the mouse correct its behavior on the next trial if the animal had been using that specific stimulus to guide its decision. If the stimulus was one the mouse was ignoring, the extra dopamine jolt had no effect. This was the smoking gun: dopamine in the DLS acts as a highly specific, context-aware teaching signal, reinforcing neural connections only when they are relevant to the individual’s current strategy.

These biological findings inspired the researchers to develop a new computational framework called the "Tutor-Executor" model. Unlike traditional reinforcement learning (RL) models in AI that update values globally, this new architecture incorporates "partial, input-specific" teaching signals. It successfully replicated the diverse learning trajectories, early biases, and even the learning plateaus observed in the mice. The model revealed that these plateaus correspond to "saddle points" in the learning landscape—unstable phases where the brain is transitioning between strategies. This computational approach provides a powerful new tool for understanding how the brain navigates the complex path from novice to expert.

The implications of this research extend far beyond the laboratory. By understanding dopamine as a personalized teaching signal, we can gain new insights into a range of neurological and psychiatric conditions where reward-driven behavior is altered, such as addiction, depression, Parkinson’s disease, and ADHD. It opens the door to developing predictive models and therapeutic strategies based on an individual’s unique behavioral and dopaminergic patterns.

Furthermore, these principles could revolutionize artificial intelligence. By building AI with more biologically plausible learning mechanisms, we could create systems that are more adaptive and efficient. Imagine educational software that tailors its teaching style to your specific learning strategy, or training programs that help you overcome personal plateaus more effectively. This research brings us one step closer to a future where technology can learn and teach in a way that mirrors the brain’s own elegant, personalized methods.

Ultimately, this work transforms our understanding of a fundamental biological process. Dopamine is not just a simple motivator; it is the brain’s master sculptor, carefully shaping our neural clay based on our unique experiences. It explains why each of our learning journeys is our own, complete with its distinct challenges and triumphs, and it highlights a profound synergy between the mechanisms of learning in animals, humans, and even our most advanced machines.

Reference

Liebana, S., et al. (2025). Dopamine encodes deep network teaching signals for individual learning trajectories. Cell, 188, 3789–3805.e33.