A groundbreaking study peers into the brains of young athletes, revealing how years of contact sports trigger inflammation and neuronal damage—the potential seeds of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE)—long before symptoms emerge.

From the roar of the crowd under Friday night lights to the intense focus of a collegiate boxing match, contact sports are a cornerstone of athletic culture. For decades, the primary concern surrounding head safety in these sports has been the concussion—a jarring, symptomatic brain injury that demands immediate attention. But a more insidious threat has been gaining recognition in the scientific community: the cumulative effect of repetitive head impacts (RHIs), the thousands of smaller, sub-concussive hits an athlete endures over a career. These impacts often go unnoticed, without the dramatic signs of a concussion, yet they leave a mark. The crucial question that researchers have been racing to answer is, what exactly is that mark? What is happening at the microscopic, cellular level inside the brains of young, seemingly healthy athletes?

A pioneering new study, highlighted in Nature Reviews Neuroscience, provides some of the clearest answers to date. By examining post-mortem brain tissue from young individuals exposed to RHIs, a team of researchers led by Butler et al. has created a detailed map of the earliest cellular changes that may pave the road to devastating neurodegenerative diseases like CTE.

Peering Inside the Cellular Machinery

To understand the subtle damage caused by years of impacts, the scientists needed a tool of incredible precision. They turned to a cutting-edge technique called single-nucleus RNA sequencing. In simple terms, this method allows researchers to isolate an individual cell’s nucleus—its command center—and read its active genetic playbook. It reveals which genes are turned on or off, providing a snapshot of that cell’s function, health, and state of distress. It’s like intercepting the internal memos of every type of cell in a specific brain region to see how they are reacting to their environment.

The research team analyzed cortical tissue from three distinct groups: young individuals (under 51 years old) who had a history of RHI exposure and had developed the initial pathological signs of CTE, young individuals with a similar history of RHI exposure but no CTE pathology, and a control group of individuals with no history of contact sports. This design was critical, as it allowed them to isolate the changes caused by head impacts themselves, even before a disease like CTE becomes fully established.

The Brain’s Immune System on High Alert

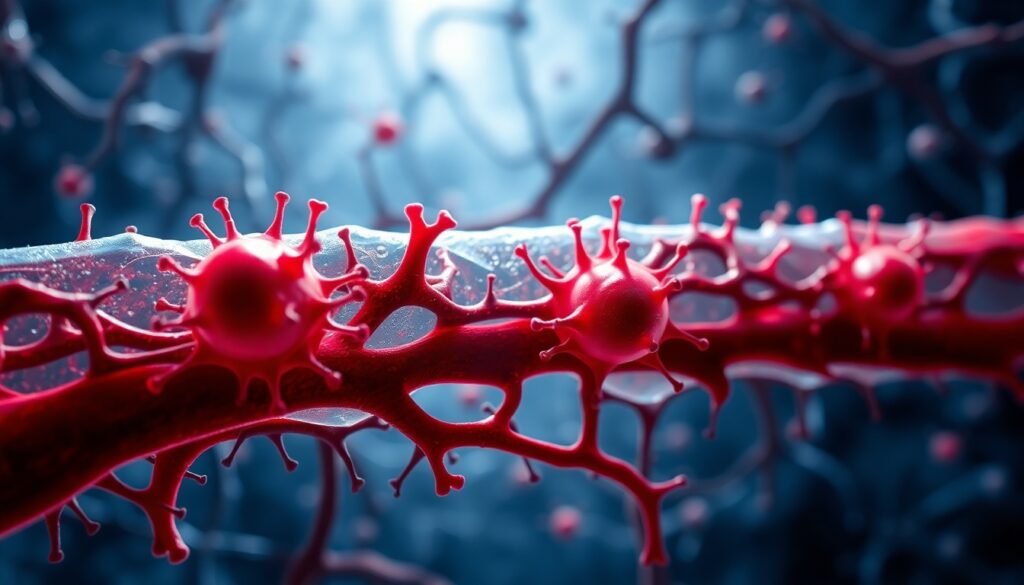

The study uncovered a dramatic and dose-dependent response within the brain’s support and defense systems. Two key cell types were thrust into the spotlight: microglia and endothelial cells. Microglia are the brain’s dedicated immune cells, acting as a combination of janitor and security guard. They clean up cellular debris and respond to injury or infection. Endothelial cells form the lining of the brain’s vast network of blood vessels, creating the crucial blood-brain barrier that protects it from harmful substances.

The researchers found a direct correlation: the more years an individual had spent playing contact sports, the more their microglia shifted into an inflammatory state. The genetic playbook of these cells showed they were ramping up the production of inflammatory molecules. Essentially, the repetitive impacts were putting the brain’s security guards on a permanent high alert. While this inflammatory response is helpful in the short term to deal with an acute injury, a chronic state of inflammation is toxic to the delicate neural environment. It’s a fire that, left to smolder for years, begins to damage the very structures it’s meant to protect.

Similarly, the endothelial cells lining the blood vessels also began expressing inflammation-related genes. This suggests that the integrity of the blood-brain barrier may be compromised, further contributing to a harmful and unstable environment within the brain.

Damage to the Communication Network

While the inflammatory response was a major finding, the study also revealed direct consequences for the brain’s primary communicators: the neurons. The analysis showed that RHI exposure was significantly associated with two alarming changes. First, there were alterations in genes related to synapses. Synapses are the microscopic connections between neurons, the junctions where information is passed. The proper functioning of these connections is fundamental to everything the brain does, from forming a memory to executing a movement. Altered synaptic genes suggest this intricate communication network is being destabilized and weakened.

Even more troubling was the second finding: an outright loss of neurons. The cumulative effect of the head impacts was linked to the death of brain cells. This is the most direct form of brain damage, a physical erosion of the brain’s processing power. The combination of a toxic, inflammatory environment and destabilized synaptic connections appears to create a situation where neurons simply cannot survive.

These findings paint a coherent and disturbing picture. The journey toward CTE may not begin with the disease’s signature protein clumps (tau tangles) appearing out of nowhere. Instead, it may start years, or even decades, earlier with a smoldering fire of inflammation and a slow, steady degradation of the brain’s wiring. The repetitive hits sustained in youth sports appear to be the spark that lights this fire.

Redefining Risk and Prevention

The implications of this research are profound. It shifts the focus from the single, symptomatic concussion to the total, cumulative burden of head impacts over a career. The damage is dose-dependent—the more years you play, the greater the cellular disruption. This provides a biological explanation for why some athletes develop CTE while others playing the same sport do not; exposure levels and individual resilience likely play a key role.

These findings underscore the urgent need to rethink safety protocols, particularly in youth and amateur sports. If the cellular seeds of neurodegeneration are being planted in young athletes, then strategies must focus on limiting total exposure. This could mean rule changes, fewer contact practices, and the development of better protective gear that doesn’t just prevent skull fractures but lessens the transfer of rotational and linear forces to the brain.

Furthermore, this cellular blueprint of early-stage damage could pave the way for new diagnostic tools. Imagine a future where a blood test could detect biomarkers of this specific inflammatory response in the brain, allowing for early intervention and informed decisions about an athlete’s career and long-term health. For now, this study is a stark reminder that even when there are no outward symptoms, the brain is keeping score. Every hit counts, and the unseen toll at the cellular level may be the most important one of all.

Reference

Whalley, K. (2025). Cellular responses to repetitive head trauma. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41583-025-00977-4