Explore the rare condition of hyperthymesia, where individuals recall their life in vivid detail, and what it teaches us about the very nature of memory, identity, and consciousness.

What were you doing on this exact date five years ago? For most of us, the question is impossible to answer with any certainty. Our memories of the past are fluid, selective, and often hazy. We remember significant events—graduations, weddings, the birth of a child—but the mundane details of an average Tuesday tend to fade, merge, or disappear entirely. This is the dynamic, and frankly, practical, nature of human memory. It filters, rewrites, and lets go.

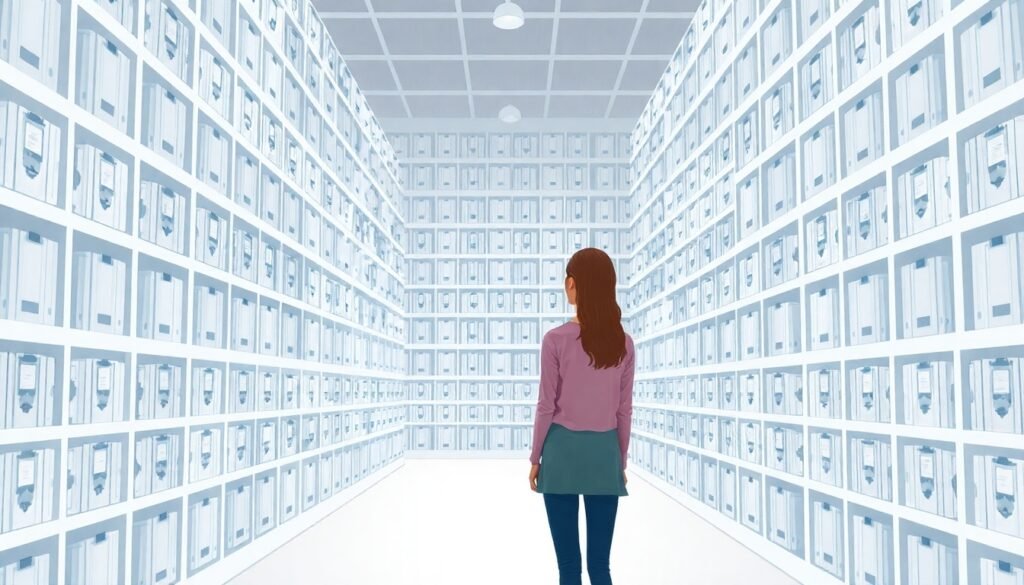

But what if it didn’t? Imagine a mind where the past is not a distant, foggy landscape but a meticulously indexed library, where every day is a book that can be opened and relived with startling clarity. This is the reality for a handful of individuals with hyperthymesia, or Highly Superior Autobiographical Memory (HSAM). These are people who can, upon hearing a date, recall precisely what they did, who they were with, and even how they felt on that day. Studying this extraordinary ability offers a profound glimpse into the mechanics of memory and its deep connection to our sense of self.

A Mind That Travels Through Time

Autobiographical memory is the cornerstone of our personal narrative. It’s a collection of experiences, emotions, and facts that together form the story of our lives. This ability is tied to what scientists call “autonoetic consciousness,” a uniquely human skill that allows us to mentally travel through time. We can revisit a past moment, project ourselves into a future scenario, or even construct imaginary worlds. For individuals with hyperthymesia, this mental time machine operates with extraordinary power and precision.

“In these individuals, known as hyperthymesics, memories are carefully indexed by date. Some will be able to describe in detail what they did on July 6, 2002, and experience again the emotions and sensations of that day,” explains Valentina La Corte, a research professor at Paris Cité University. This isn’t just recalling a fact; it’s a full-sensory reliving of the moment. While this sounds like a superpower, it’s often described as a heavy burden. Many with hyperthymesia report feeling overwhelmed by an uncontrollable flood of memories, both trivial and traumatic. The inability to forget means that painful experiences can remain as fresh and sharp as the day they happened.

Organizing the Unforgettable: A Mental Memory Palace

This is what makes the case of TL, a 17-year-old girl studied by La Corte and neurologist Laurent Cohen, so fascinating. She appears to have developed a remarkable system of control over her vast repository of memories. TL doesn’t just have a flood of recollections; she has a filing system. She describes her mind as a sophisticated “memory palace,” a mental space she can navigate on demand.

Within this palace, a central space she calls “the white room” holds binders that chronologically and thematically organize her life events: family, friends, holidays, and childhood. To access a memory, she mentally visualizes herself scanning these binders. But her system is more than just organizational; it’s emotional. TL uses her mental architecture to manage the psychological weight of her memories. For instance, the painful memory of her grandfather’s death is secured away in a chest inside the white room. She has also constructed adjoining rooms to process specific feelings: a “pack ice” room to cool her anger, a “problems” room for quiet reflection, and even a “military room” populated by soldiers, which her mind created when her father left for the army.

TL’s case challenges the notion that hyperthymesia is an entirely passive and uncontrollable condition. Her intricate mental palace suggests a high level of cognitive and emotional management, turning a potential burden into a structured, navigable internal world.

Studying the Past to Understand the Future

How can scientists verify such a subjective experience? Researchers face the challenge that, like anyone else, hyperthymesics are susceptible to false memories and distortions. To objectively assess their abilities, scientists use specialized tools like the Episodic Test of Autobiographical Memory (TEMPau). These tests confirmed that TL relives her past with exceptional intensity and vividness, able to re-examine events from multiple perspectives, sometimes as a protagonist and other times as an external observer.

Intriguingly, her ability extends forward in time. When asked to imagine future events, TL provided descriptions rich with temporal, spatial, and perceptual detail, far exceeding what a typical person can conjure. This reinforces a growing theory in neuroscience: the same brain mechanisms we use to remember the past are used to construct our vision of the future. Our ability to plan, dream, and anticipate is fundamentally built upon the foundation of our past experiences.

The Unanswered Questions

Despite these insights, hyperthymesia remains largely a mystery. Some studies suggest it’s associated with overactivation in brain networks related to memory and vision, yet no consistent anatomical differences have been found in the brains of hyperthymesics. Is there a genetic component? A potential link to synesthesia—a condition where senses are blended—has been proposed, as several of TL’s family members are synesthetes, though she is not.

Because only a handful of cases have ever been documented, it’s difficult to draw broad conclusions. “Does ageing affect the memories of these individuals? Do their mental time-travel abilities depend on age? Can they learn to control the accumulation of memories?” asks La Corte. “We have many questions, and everything remains to be discovered. An exciting avenue of research lies ahead.”

Hyperthymesia is more than a neurological curiosity; it’s a window into what makes us who we are. It forces us to consider the delicate balance between remembering and forgetting, and how that balance shapes our identity, our emotions, and our journey through time. For those who cannot forget, the past is never truly past—it is a constant, vivid, and ever-present companion.

Reference

La Corte, V., Cohen, L., et al. (n.d.). Autobiographical hypermnesia as a particular form of mental time travel. Neurocase.