How Your Brain Juggles Survival and Suffering—And What That Means for the Future of Pain Relief

Chronic pain is a life-altering condition that grips nearly 50 million Americans, often persisting for years and outlasting its original cause. For countless sufferers, this pain is invisible—without an obvious injury—and stubbornly resistant to medication or therapy. However, groundbreaking research from the University of Pennsylvania and collaborators may have identified a surprising switch within the brain that helps explain why, in moments of hunger or fear, pain sometimes takes a backseat. Now, scientists are examining how this discovering could transform our understanding and treatment of chronic pain at its source: the brain’s own internal circuitry.

The Dual Nature of Pain: From Protective Reflex to Endless Alarm

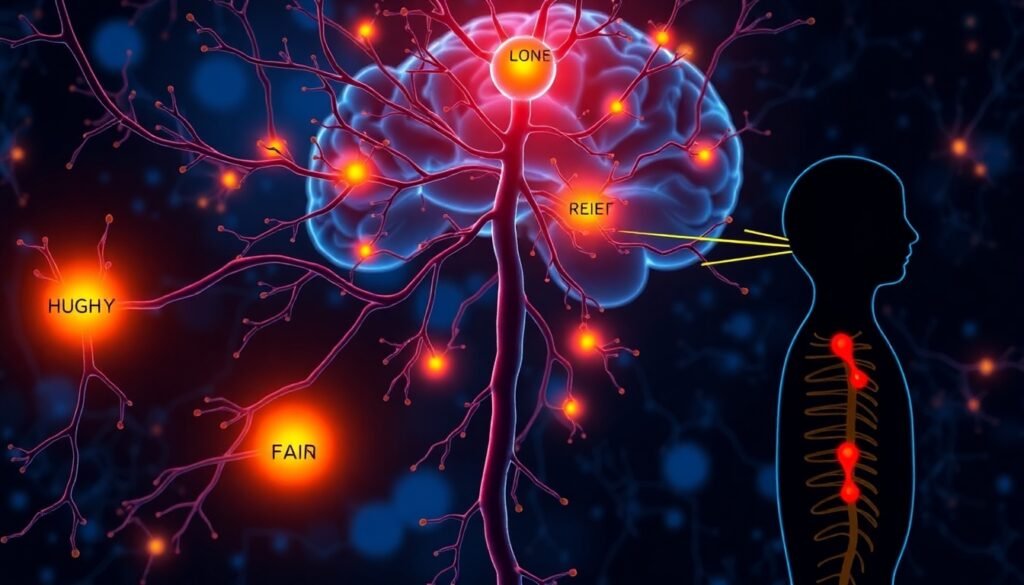

Pain, for most of us, is a crucial warning light. Stub your toe or touch something hot, and your nervous system shouts a quick, unmistakable “Ow!” This acute pain is short-lived—a teaching moment from our biology, ensuring we avoid future harm. But chronic pain is a different story. Instead of a fleeting response, the alarm persists long after bodily harm has healed. The pain itself becomes the problem—gnawing at daily life, disrupting movement, and sapping mental energy.

Until now, treatments for chronic pain have often targeted the site of injury or focused on numbing the nerves responsible for relaying pain. But what if the real source is not in the muscles, bones, or nerves, but in our brains, in how it decides which signals matter most?

Meet the Brain’s Pain “Override Switch”

A discovery led by J. Nicholas Betley’s team at the University of Pennsylvania sheds light on an internal circuit that can quiet the chorus of pain when the stakes are high. The secret lies in a cluster of cells known as Y1 receptor (Y1R)-expressing neurons nestled within the lateral parabrachial nucleus (lPBN) of the brainstem. These special neurons act as a crossroads for the brain’s assessment of multiple needs—from hunger and thirst to fear and, crucially, pain.

Using real-time calcium imaging, Betley’s group studied how these Y1R neurons behave in animals experiencing both acute and lingering pain. They found that the cells don’t just spark during those sharp, momentary hurts. In the case of chronic pain, these neurons keep up a steady stream of activity—like an engine idling long after the warning light should have shut off.

But here’s the twist: when animals were intensely hungry, or when their brains were confronted with signals of thirst or danger, these same neurons dialed down the pain. It was as if the brain had a built-in override switch—prioritizing immediate survival over lingering discomfort.

Neuropeptide Y: The Messenger Molecule

How does the brain pull this off? Through a signaling molecule called neuropeptide Y (NPY). When hunger or fear become urgent, other neurons release NPY, which binds to the Y1 receptors in the brainstem. This direct interaction dampens ongoing pain signals, allowing more pressing needs—like escaping a predator or seeking food—to take center stage.

“This is the brain’s way of saying: if you’re starving, or running for your life, you simply can’t afford to be overwhelmed by pain,” explains Nitsan Goldstein, co-author of the study.

Not One Type of Neuron, But Many

Interestingly, the researchers discovered that these Y1R neurons aren’t gathered into a tidy group. Rather, they are scattered like yellow cars throughout a parking lot of many other vehicles, distributed among diverse cell types. This wide distribution may enable the brain to turn down different kinds of pain across multiple circuits—offering a versatile and flexible approach to pain management.

Implications for Chronic Pain Treatment: A Shift to the Brain’s Circuits

The big breakthrough here is that chronic pain may persist not because of damage at the site of injury, but because these internal brain circuits are hyperactive and can’t turn themselves off. This challenges the dominant approach in pain medicine, which often focuses on treating the body instead of the brain.

“If we can measure the activity of these Y1R neurons as a biomarker for chronic pain, we give drug developers and clinicians a powerful new tool,” Betley notes. For patients who live with pain despite apparently healthy nerves and tissues, this could finally offer answers—and hope.

Beyond pharmaceuticals, the findings also suggest that behavioral interventions—like exercise, meditation, and cognitive behavioral therapy—could influence the same neural pathways as the hunger, thirst, or fear that switched off pain in the lab. If the brain’s override switch is flexible, future treatments could be engineered to harness both biological and learned inputs.

Looking Forward: From Pill to Practice

What excites researchers most is this newly revealed flexibility in the brain’s own pain circuits. While there is certainly potential for the development of drugs that act on the Y1R-neuropeptide system, a future vision includes behavioral therapies, lifestyle changes, and even training that could help recalibrate the brain’s prioritization system for people living with chronic pain.

In other words, the answer to decreasing pain may not lie only in stronger medicines or more invasive treatments. Instead, it may be possible to teach the brain new ways to filter pain, making life’s more urgent needs—and pleasures—shine through the suffering.

Reference

Betley, J. N., et al. (2024). A parabrachial hub for need-state control of enduring pain. Nature.

University of Pennsylvania. (2024). Hunger, Fear, and the Brain’s Hidden Switch to Turn Off Chronic Pain. Neuroscience News. https://neurosciencenews.com/hunger-fear-pain-brainstem-29792/